Views: 853

New series of articles: “Post-COVID’s” effect on national and European growth

Establishing of a new line of EII’s research “block” is a reflection of the Institute’s interest in the changes in modern European political economy’s policies and in the “post-COVID’s” effects on European socio-economic integration, workforce and governance.

The Institute is quite aware that sooner or later the present pandemic will come to an end; but the attention to urgent national efforts in re-shaping political-economy’s structures and formulating adequate measures in tackling any critical situations and/or disasters in future would be always vital both for researchers and for the governance.

Hence, the EII’s series would cover most vital and –hope – most interesting for our readers “post-pandemic issues”, which could be actually quite numerous. However, the Institute’s focus will be on those political-economy’s issues which are having direct (mostly) and indirect (consequently) effects for the European integration and the perspective growth in the member states. Some initial signs of EEI’s interest in these issues can be seen at: https://www.integrin.dk/2020/04/14/after-covid-composing-a-resilient-economys-plan/#more-392

The series’ concept

Complexity of this line of research is evident: so far major remedy efforts during the pandemic have been dominated by the medical and biological sciences (as the main instruments to resolve the infection’s spread); hence, among most pertinent means in treating the pandemic were quantitative easing and additional financing. This has been a vision in the EU’s long-term approach as well, i.e. a massive financial injection into numerous rescue measures in the multi-annual budget and the “new generation EU” rescue program, both totaled about € 1, 82 trillion.

Several scientific disciplines are already involved in researching the pandemic’s aftermath. However, a vital remark has to be made: contrary to the natural sciences’ fields (including medicine and biology), in which there are fundamentally accepted “rules” guiding each sectors’ evolution and development, in social sciences (incl. economics and politics) that “set of rules” is not so-to-say universally evident; in many cases scientists in the world are still in doubt about their proper application.

It doesn’t mean though that the lack of formally adopted and recognized “rules” in social sciences has limited the role of the sciences’ impetus into a better understanding of basic human life’s circumstances along with guidelines on which an evolving modern political economy is based. Therefore, the Institute’s set of “post-covid” articles is aimed at providing a new vision into political analysis while visualizing additional instruments in understanding “the changing rules” and formulating most feasible approaches to growth models and, in the last extent, in predicting the future trends in the European integration.

The pandemic is still “covering” major parts of the world and Europe: by the mid-2020, there were about 700,000 deaths recorded from the pandemic, and the global-total is increasing at a rate of roughly 40,000 a week; with unrecorded deaths, the actual numbers could be higher. Meanwhile, the global economy is experiencing its sharpest contraction since the Great Depression a century ago, of about 8% of GDP in the first half of 2020; shutdown in Europe coasted millions of jobs followed by the greatest ever contraction (e.g. in the UK over 20 percent). Source: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2020/08/08/the-world-is-spending-nowhere-near-enough-on-a-coronavirus-vaccine

Hence, the series’ scope – at least in the initial period – would consist of three main parts (with a number of articles in each) stemming from the necessity to reveal present conditions and perspectives in three most vulnerable to the national growth patterns and the European integration issues: a) economy and entrepreneurship, b) workforce and labour relations/markets, and c) politics and governance. These three lines of research will be closely connected to the systematic vision of the EII’s new “post COVID” research activities: the Institute intends to follow closely the “post-Covid” changes in subsequent publications.

a) Business and entrepreneurship

During the first half of 2020, corporate entities and employers in general have been trying to adapt to unexpected and new strategies while trying to implement them in the two main directions: a) in working processes and staff, ensuring employees participation; and b) in adaptation to digital technologies, AIs and robotics.

In entrepreneurship, as it seems, is important to take into consideration peoples’ life styles, habits and consumption patterns in view of great modifications occurring in consumers’ behavior, while being better prepared for a continuously changing consumers’ “tastes”.

For any business it is vital to understanding the main “features” that are driving consumers’ shopping instincts: these are the key factors which businesses need to consider when approaching consumers. Several key consumer types have been explored recently, from lifestyle choices to buying habits, with their effect on consumers and business interrelations.

More in: Euromonitor International: Top 10 Global Consumer Trends 2020, by Gina Westbrook and Alison Angus: http://go.euromonitor.com/rs/805-KOK-719/images/

At the same time, changes are expected in the corporate internal structures, where remaining agile is becoming ever vital together with broader corporate social responsibility, CSR.

b) Workforce and labour relations/unions

This part of research consists of a number of sub-sections: in the first place, the attention is directed towards analysing changes in the workforce and labour markets in general, with the apparent need for new skills and job’s opportunities. Affordable digital professional skills would provide people with a better life and personal accomplishments while assisting in making better decisions on possible future perspectives.

However, with modern global and European challenges, e.g. with technological and digital transformations, the “images of the future” would have to require a constant impetus of new skills and/or fundamental retraining. This can increase peoples’ capacity to withstand possible difficulties in life. Among new skills, a digital literacy is becoming a priority alongside “teaching sustainability” and additional need in the system thinking; the quality teaching and learning is a key to a changing workforce.

Besides, the Institute will analyse the present situation in the European labour market and trade unions as major factors in the EU’s guidelines towards “social market economy”. Recent pandemic has underlined a vital new aspect in the labour union’s functions leading to quick and necessary changes in the existing system: the unions to survive shall see a modern “dilemma” – i.e. between an individual and union’s “interests” in collective bargaining. The problem is huge for a lot of workers: thus, only in Denmark about 600 thousand employees in private labour market are facing this sort of issues. Existing system in some Nordic states doesn’t take so far the individual interests in the tripartite bargaining (among business, unions and government). Recent analysis has shown that about 43% of workers in private sector would rather make “individual arrangements” than go through collective bargaining.

c) Political economy and governance

Generally, to handle the pandemic’s aftermath, global and national governance structures have to change traditional decision-making with a view to tackle modern challenges. Although the pandemic is mainly a health problem, it also “shaking” the society’s basic pillars connected to politics and economics. Hence, major challenges in national governance in “after-pandemic” are those of an “unpredictable world”, getting ready for changes and able to use new priorities followed by improvements delivered by dramatic social and technological transformations. Therefore, the issues of incorporating the “challenging priorities” are to be the first in the list of the national governance measures. Reference to: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/08/

Attention to politics and governance’s needs a complex and systematic approach. Thus, almost all the challenges associated with the “post-COVID” syndrome are based on systematic analysis of expected changes in e.g. such issues as: a) the scope and function of “modern governance”, b) the “civil-servants-revolution” and the states’ integral parts, and c) relationships in the political economy’s system. Thus, systematic approach helps to understand the “whole picture” and effective modernisation of existing governance’s structures.

Bottom line: Predicting the future needs a strategic vision; modern challenges require decision-makers to understand the “signals” of potential threats. The researchers’ task – in advising national and the EU’s governance – is to provide empirical evidences of the needed changes and transformations even if at present these “evidences” (as well as decisions) are neither clearly seen nor commonly adaptive.

In this regard, new “consultative skills” could be recognized as a vital instrument in creating a “futuristic vision”. Numerous contemporary disruptive changes are already requiring both the events’ scientific analysis and drafting decisions to withstand the evolving growth patterns.

Therefore the main series’ idea is to turn the post-covid’s “remedy situation” to the economic advantage: in this sense, researchers require both new approaches in analytical “instruments” and in strategies for the governing elites to draft perspective economy, entrepreneurship and a workforce – all of which would be quite different from the existing patterns.

Thus, for the decision-makers it is not enough just “to better understand” changes; ultimately, researchers have to give “good recipes” to all those that need them! As to “instruments”, a new scientific discipline shall be envisaged: so-called “strategic future studies with a strategic foresight”. More generally, “futures studies” is a discipline that would broaden the exploration of alternative futures and deepen the investigation of the worldviews that underlie possible and preferable decision-making.

The Institute’s research is based on the assumption that the future is both a continuity of “the present” towards a better understanding of changes and multiplicity of the future scenarios; all that would allow a modern researcher to develop future-proof strategies that anticipate the consequences of alternative governance’s actions. Actually, a cultural leap from a reactive approach to an anticipatory one is needed too; this will only be possible if the decision-makers and those reading our articles would manage to embed the ideas mentioned in publications into the new knowledge and skills to be incorporated into governance strategies.

Today, the states and the civil societies may grab the great chance for a breakthrough which could bring them all to a better Europe with sustainable economic systems and increasingly mature societies. That is the best vision for a European Union’s integration, where the member states would cooperate closer to make people safer, happier and healthier…

Workforce after pandemic: the process of continuous reforms

The “post-pandemic” disruption has dramatically affected a seemingly stable employment’s basic fabric; modern political economy shall include in their strategies new trends in the evolving workers’ socio-economic issues. By developing new political and economic models, all already apparent and not so clear changes on employment and workforce’s issues affecting the labour market shall be taken into consideration. Complexities of the needed reforms involve the multiple effects of the digital and “green growth” transformations on present governance and decision-making.

Dramatic transformations in workforce through the present pandemic have become a serious problem for the governance and the humans. Both are facing with an unprecedented task, i.e. to accommodate the age-old quest for job with the “meaning of life”, the sense of community and new growth pattern; and all that under disruption by the post-pandemic outcomes…

For a proper understanding of the labour market changes, the “social actors” and decision-makers have to take into consideration at least two issues: a) generally new trends in the labour market, and b) consequential changes in the labour unions; both issues will be dealt with in the EII’s publications.

About the Institute’s research project concerning the “life after pandemic’s” issues in: https://www.integrin.dk/post-covids/. The first article in the series can be seen at:

https://www.integrin.dk/2020/09/11/post-covids-political-economy-facing-inevitable-changes/

Labour market: five things one shall know about modern transitional complexities

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the new trends in the employment structures and the labor market have shown the need for “accommodating” the old employment perceptions to new ones, requiring the need for changing approaches to education and training, with the attention to digitalisation, artificial intelligence (AI) applications, as well as to changes in corporate strategies and national growth priorities.

Besides, a novice labour issue has become of utmost importance in the “post-pandemic” area: the “working life has entered a new era”, which signified a historic-type transformation from a “farewell BC” (before coronavirus) to a “welcome AD” (after domestication).

Source: the Economist (28.05.2020/Bartleby), in: https://www.economist.com/business/2020/05/28/working-life-has-entered-a-new-era

Some trends are already visible in the perspective labour market transformations; among them are the following “five things”:

– “Labour image” is getting more personal and social: young graduates are being intensively looking for jobs in companies delivering on innovation, social responsibility and sustainable growth. In this way “new labour” could meet two ends – a personal carrier and corporate values; therefore in future, most young workers will stick to occupations connected to sustainable growth.

– Labour markets are affected by demographic changes: e.g. in the Nordic countries presently life expectancy reached 79 for men and 83 for women; that brings more seniors into employment. Although a retirement age is increasing in Europe, it is making about 25 years or so in active work to get a sufficient retirement.

– Flexible employment strategy enters national labour market policy with the apparent changes from a “fixed-for-life” employment to a kind of “non-typical” working conditions. It is becoming a common place to combining several occupations and a freelance employment (pro bono type) as part of “lose-structured” workforce. The long-term isolation during pandemic only signified the fact that some citizens would never return to their previous jobs, and that they would rather be “their own masters” and work from home…

– Increasing need for various types of digital skills: previous so-called “traditional functional competences” shall be fundamentally changed, and re-skilling shall be a “new norm” for most workers. That could also mean that through the employment career a successful worker shall be re-trained four-fife times. Besides, corona-epidemics have shown that the main direction in such re-training shall de along the digital science and technology transfers.

– Some new professions shall appear in teaching, training and proficiencies, e.g. dealing with the business technology, corporate social responsibility, and management processes using algorithms and other software means finding solutions through closer cooperation cross-functional teams with the customers. Greater role of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics is finding way in the entrepreneurship culture and business technology: the ideal AI can help to rationalize and take actions to achieving better results as algorithms –in association with a human mind –can be best both in learning and problem-solving. Presently, the AIs include a number of “human-business abilities”, such as learning, reasoning, perception, behavior and decision-making, etc. being successfully employed in different industries including finance and healthcare.

Digitalization’s effect

In an effort to resolve a modern “digital vs. traditional work” dilemma, one has to remember that humans originally possess two kinds of “abilities” –physical and cognitive; the latter is connected to perceptions, awareness, emotions and judgment. Contemporary digital appliance and algorithms, including artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics outperform humans in an increasing number of skills and professions. Hence, the humans’ dominance in the labour market is under constant threat to be substituted by “wise & clever” machines. Modern science, however, has revealed that several so-called “sovereign” human abilities (i.e. emotions, desires, preferences and choices, to name a few) are nothing else than just bio-chemical reactions in human brains, which can be performed by AIs and even in a much better and efficient mode; hence, the appearance of such research directions as behavioral economics active “accumulation” of human perceptions by online advertising services, e.g. Facebook or LinkedIn.

It’s true: the neuron-physics and brain researchers have established that behind human decisions as consumers, for example, is the result of neurons combination’s activities, which can be in principle turned into biochemical algorithms. In this way the AIs can not only outperform humans in some kind of “emotions and intuitions”, but calculate options and probabilities and making human “work” obsolete by computing into algorithms human abilities, and making all that better, efficiently and quicker! That is another line of perspective research: combining ICTs with bio-technologies, which would outperform in future such previously regarded as unique the workers’ abilities of connectivity and updatability… Even such spheres of human dominance as music composition can be rather easily turned to AI: an appropriate algorithm can transform “input & output” into a computer program; using a person’s biometrical data, algorithms melodies “compose” a personalized tune.

It is obvious that some professions are more susceptible to AIs: e.g. physicians (in diagnosing known diseases and managing familiar treatments), pilots on local lines (by using drones), banking assistants and accountants, etc. showing a perspective trend of “cooperating” humans with AIs and algorithms.

With the help of AIs, it would be easier to create new jobs than providing a constant vocational retraining; the perspective that is already visible presently with unemployment and a shortage of needed skills. Besides, the “labour volatility” can make it difficult for labour unions to secure membership as many new jobs are taken by freelances and temporary workers; with professions which are quickly rotating once a decade, the unions shall be quickly adapting adequately… In a couple of decades “professions-for-life” would be useless, and jobs on one place for entire life even more improbable.

All the digital impacts, as well as that of AI and robotics, could be unpredictable for the workforce and socio-economic development; however, the positive outcomes would depend on both the cultural traditions and political environment: due to some reasons, even the most promising (visually) decision-making could be nevertheless blocked by political-economy’s interests and disruptions.

More in: Harari Y. N. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Spiegel & Grau, New York, 2018. Chapter “Work” (pp. 19-43)

Reducing youth unemployment

The problem is serious enough: youth unemployment in the EU states is twice as high as the general unemployment. The decision-makers have to realize that a quick and smooth transition into a first job is essential for young people’s careers and working lives. However, the economic recession as a result of COVID-19 has affected the younger generation in particular, disrupting their education and their entry into the jobs market.

Entry-level jobs have largely disappeared and recruitment processes are being delayed. Among the urgent issues are the ones to support effectively young people’s transition to work during the pandemic – and beyond – and contribute to a more inclusive recovery. With this objective in mind, the European Commission presented already in July 2020 a youth employment support package “A Bridge to Jobs for the next generation”.

Moreover, during the German Council Presidency in the second half of 2020, some key decisions were adopted such as the reinforced Youth Guarantee, the Skills Agenda, and a proposal for a Council Recommendation on vocational education and training.

It is recognized that implementation is the key to success; thus partners from a European “StartNet project” decided to share their experiences and feedback for improved policies and practices with a view to providing all young people with the opportunities they deserve. Four key issues are covered: social inclusion, orientation and career guidance, key competences, vocational education and apprenticeships.

Note: StartNet Europe provides a European platform connecting initiatives on young people’s transition from education to employment from Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Romania, Slovakia, Spain and Switzerland. The aim is to exchange good practices, to learn how to overcome common challenges and to support collective goals and interests. Source:

https://www.start-net.org/en/startnet-europe

Changes in the labour market

During last two decades, i.e. since 2000, both spending on travel, food, and entertainment, as well as employment in leisure and hospitality (the large category including restaurants, hotels, bars and amusement parks) have been increasing three times faster than the rest of the labor force. Now the situation has changed dramatically: the rise of home-bound workers increasing more than anything else at the expense of other “sectors”. Most in business follow the old pattern: “travelling” from home to a workplace; now the pattern is changing as home has become a workplace…

Emptier offices mean fewer weekday lunches at restaurants, fewer happy hours, as well as fewer window shoppers, not to mention less work for office buildings’ cleaning, security, and maintenance services; just as it happened in retail: Amazon with e-trade has changed the old “shopping habit” for good. Curious enough, the UK’s government labour office is called now the Department of Works and Pensions!

Unemployment in the first half of 2020: In the euro area the unemployment rate increased for the fourth consecutive month, to 7.9%, with increases of 0.3 percentage point or more in France, Ireland, Italy and Portugal. The OECD youth unemployment rate (people aged 15 to 24) remained 4.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the pandemic but still more than twice as large as for the over 25-year-olds.

Many companies have discovered that their employees feel overworked and under-productive, emotionally depleted, and existentially exhausted. Although some of that is COVID-19 fallout, it’s also the case that people feel more alone in part because, literally, they are. Working from home has weakened both the connections to the office and to the world outside the offices.

Remote experiment through LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter, to name a few, has weakened the bonds between workers within companies and strengthened the connections between some workers and professional networks outside the company. References to: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/just-small-shift-remote-work-could-change-everything/614980/

In short, a new entrepreneurship is born: with ambitious engineers, media makers, marketers, PR people, etc.; most are inclined to be on their own in order “to monetize on their independence”. Remote work weakens traditional workforces’ bonds; although the consequences of that are not yet fully known, the immediate side effect is clear –a lot of office premises are on massive lease!

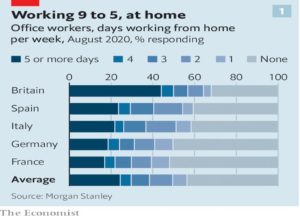

For example, in the UK only 34 percent of office workers are presently working in their normal location (according to Morgan Stanley); in France, Germany, Italy and Spain the figures range from 70 to 83 percent. Besides, in London, nearly half of office staff is working from home five days a week, compared with just 20-30 percent in the financial hubs of greater Paris, Frankfurt, Milan and Madrid.

During the last decade of the digital technologies’ proliferation, e.g. artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, cloud and blockchain, to name a few, a new sphere of research and analysis has emerged about the “employment’s future”. During several previous centuries “work” was largely understood in terms of the technological transformations with the appearance of such “workers’ categories” as blue-collar, white-collar, industrial, agricultural workers, as well as those in manufacturing, and services. Then, a dramatic “digital revolution” since the end of XX-century has revealed that the “work” can be completely different from what was known before: e.g. numerous internet-based service companies (e.g. Uber and Swiggy, to name a few) provided people with remuneration without even being formally employed on an expanded dimension.

That’s a new reality of “rethinking work”: e.g. with expanding “social contracts”, re-writing relationships between individual worker within a company and even a society, and shifting the corporations’ role in the rapidly transforming socio-economic systems to unexpected domain. Reference to:

https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_740893/lang–en/index.html.

As the pandemic resets major work trends, so the “human resource’s” leaders, so-called HRL, need to rethink workforce and employee planning, management and performance strategies. The coronavirus pandemic will have a lasting impact on the future of work in several key ways: the imperative for HRL is to evaluate the impact of new trends on the organization’s operations and strategic goals, identify which would require immediate action and assess to what degree these trends change pre-COVID-19 strategic goals and plans. Just an example: about 32 percent of organizations in developed states are replacing full-time employees with contingent workers as a cost-saving measure… More in: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/9-future-of-work-trends-post-covid-19/

As a new trend, increased remote working has been apparent even before the pandemic, i.e. due to digital transformation; with the COVID-19, about half of the employees will work remotely versus about 30 percent before. Shift to remote work-pattern would force employees to get used to new type of work condition and circumstances, which would require fundamental retraining to be fully equipped for a “remote context”. Employers’ attitude would change adequately: from new technologies to monitor their employee’s engagements: e.g. through virtual “clocking” and tracking computer usage, to monitoring employee emails and/or internal communications.

As to “work expansion” versus cost-saving measures, companies would still expand the use of “contingent workers” to maintain more flexibility in workforce management in post-COVID and introducing new job models: e.g. “pay for a piece of work done” (replacing full-time employees with contingent workers with a new type of employment contract).

Some already predicted that within five to ten years up to 50 percent of the workforce will permanently work remotely; hence, companies’ leadership has to consider the inevitable changes and design the new workflows. As the pandemic subsidies’ increasing, there will be an acceleration of mergers and acquisitions (as well as nationalization of companies). At the same time, corporate entities would be forced to expand their geographic diversification and investment in secondary markets to mitigate and manage risk in times of disruption. This rise in complexity of size and organizational management will create challenges for leaders as operating models evolve. Source: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/9-future-of-work-trends-post-covid-19/

On-going developments such as automation and digitalisation of production and services continue to reshape the labour markets. Job-to-job transitions are becoming more frequent and many young people shift between employment and unemployment or inactivity or are trapped in precarious non-standard forms of employment. In particular, young people are overrepresented in non-standard jobs such as platform or “gig” work, which may lack access to adequate social protection. Moreover, young people are at higher risk than others to lose their jobs to automation, as entry-level jobs tend to have a greater proportion of automatable tasks.

In addition, the broader European “twin transitions” towards more digital and greener economies will offer new opportunities as new jobs are likely to be created in these sectors. However, this requires that young people have the right skills to adapt to evolving job requirements. Digital skills, skills needed for the green transition alongside soft skills, such as entrepreneurial and career management skills, are expected to grow in importance.

Investing now in the human capital will help future-proof social market economies: an active, innovative and skilled workforce is also a prerequisite for Europe’s global competitiveness.

In particular, as over 90 percent of jobs today require already digital skills, the Commission proposes to assess the digital skills of all unemployed who register by using the European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp) and the available self-assessment tools, ensuring that, on the basis of gaps identified, all young people are offered a dedicated preparatory training to enhance their digital skills.

For example, the European “green deal”, as the EU’s new growth strategy to transform the states into prosperous growth paths along modern, resource-efficient and competitive economies with no greenhouse-emissions by 2050 and where economic growth is decoupled from resource use. It puts sustainability and the well-being of our citizens at the centre of our action.

On another side, the EU’s “circular economy action plan” with cleaner and more competitive economies has set out actions to achieve the decoupling of growth from resource use by, inter alia, placing a strong focus on the need to acquire the right skills, including through vocational education and training. The transition to a clean and circular economy is an opportunity to expand sustainable and job-intensive economic activity, thus supporting recovery. Given that the greening of the economy is shaping skill requirements in multiple ways, it is crucial for the states to draft policies that will support people in harnessing the new opportunities to complement skills needed for the green economy. The strategies for SMEs shall include sustainable and digital proficiencies as already at present an increasing number of SMEs is confronted with the challenge of finding the necessary skilled staff.

Source: Communication from the Commission “SME Strategy for a sustainable and digital Europe”, COM/2020/103 final.

Entrepreneurial education and training that enhances business knowledge and skills play a key role in making SMEs fit for the competitive markets; besides, young people can be offered a preparatory training to enhance their entrepreneurial skills using the tools and modules developed under the EU’s “Entrepreneurship Competence Framework” (EntreComp).

Changing “working habits”: work-from-home, WFH

For decades people were arguing that a lot of work done in large offices shared by many could be better done at home; with covid-19 these ideas seem to have a practical outcome. This does not mean that changes are quick to come and that WFHs are here already; but debates are going on, so both the corporate entities and decision-makers have to take the issue seriously.

However, the latest data suggest that only 50 percent of people in five big EU states spend every work-day in the office, while a quarter remains at home full-time (see table below). It also appears that working from home can make people happier: a paper published in 2017 –long before the pandemic – in the American Economic Review found that workers were willing to accept an 8 percent pay cut to work from home, which suggests that it gives them non-monetary benefits.

The Economist also mentioned that governments are taking efforts in encouraging people “back to work”, which means “back to the office”, the fact that office-working must be more efficient than home-based work both for firms and for workers. By this logic the success of a country’s recovery from lockdown can be measured by the number of people back at their desks (i.e. still only about 4 percent of full-time employees in the UK usually work from home). Before covid-19 the world may have been stuck in a “bad equilibrium” in which home-work was less prevalent than it should have been. The pandemic represents an enormous shock which is putting the world into a new, better equilibrium”, the Economist argued.

For example, Gitlab, a software company, has been “all-remote” since it was founded in 2014; with no offices, it managed to gather together 1,300 “team members” living in 65 different countries (at least once a year they get together for team-bonding). Several companies, such as Teemly, Sococo and Pragli offer “virtual offices”, which is making it easier to communicate with colleagues, rather than going through a complicated system of video conferences.

Source: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/09/12/covid-19

Labour issues in politics

Socialists and democrats (PES group in the European Parliament, EP) are the most vivid supporters of the perspective labour force in the EU: this group in the EP, e.g. strongly backed the Commission’s proposal on financial support for unemployment risks that workers could receive a needed help.

More than that, a specific “instrument” has been suggested, i.e. “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency”, SURE was initiated at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis with the aim of providing about €100 billion to facilitate short time work schemes and prevent job losses during this period of economic uncertainty. Over 15 member states have already applied to SURE, amounting to €81.4 billion, demonstrating that this support is a valuable tool to meet the real needs of member states.

Thus the PES President argued that SURE was “a lifeline for member states and Europe’s workers” and that the money must reach workers and companies as soon as possible.

Socialists and democrats have been at the fore of the push for more support for Europe’s workers during this pandemic; the SURE program in the EU’s recovery plan was just a step towards a permanent European reinsurance scheme for unemployment benefits. The mechanism for preventing unemployment during the COVID crisis was included in the PES Recovery Plan, and European socialists and democrats pushed for a serious economic recovery package.

Labour movement in European integration: facing modern challenges

The labour market and trade unions in the EU as a whole and in the member states shall be seen as most important parts in the EU’s doctrine of growth based on “social market economy”, which is a different facet of traditional “capitalism”. Although the covid-pandemic has challenged and jeopardized the implementation of the ambitious EU’s green and digital transition, it didn’t undermine the core aspects of the labour unions’ role in the transformation’s process. Regardless of the differences in the unions’ density among the EU states, the “happiest” nations in Europe are a clear example of the unions’ positive role in progressive growth.

The covid-pandemic has only additionally underlined a vital aspect in the modern labour union’s issues: i.e. in order for the unions to survive they have to pay attention to mounting problems, which include a reducing role of unions in numerous EU states, changing individual employee’s expectations from the unions and the union’s “surviving” stemming from redrafting of the collective bargaining’s process, etc.

This is the second article in the EII’s complex analysis within the “post-Covid” research concerning workforce and labour relations issues; a previous one in: https://www.integrin.dk/2020/10/07/workforce-after-pandemic-the-process-of-continuous-reforms/

A general introduction to the series of articles on “post-covid research” and the “Post-COVID’s effect on national and European growth” in: https://www.integrin.dk/post-covids/

Introduction

Covid-pandemic seriously affected the role of labour/trade unions in modern European integration: abrupt working hours, temporary as well as permanent companies’ closures and massive redundancies, etc. greatly increased both workers’ unemployment and social disruption in general. The situation in most EU countries (in particular, on central and eastern regions) has become so dramatic that urgent supporting measures have been taken by the EU and the member states’ government to assist people in need. As a result, the labour movement and trade unions in the states are experiencing devastating conditions which have already affected all walks of life.

The EII provides a review of the present labour/trade union’s situation in some of the EU states while looking into possible options in the “movement” in dealing with contemporary challenges.

The EII’s position is clear: labour movement is to be regarded as an indication of the responsible state’s social position in creating a perspective national growth. One of the major tasks in modern governance is to increase employment: it means that the labour/trade unions’ role has to be increased and strongly supported.

Traditionally trade unions have been formed for securing workers’ remuneration, improvements in employment and living conditions, providing employment benefits, minimum wages, hours of work, dismissal, holidays and so on and so forth through collective bargaining and negotiations with the government authorities and employees associations; the “discussions” are usually called a “tripartite agreements”.

Through some elected representatives, the trade unions are “bargaining” during these agreements the actual workers’ conditions, i.e. typical labour contracts schemes with the employers’ entities and the government authorities. In this way, the trade unions are not only negotiating labour contracts’ basic terms with the employers, but becoming an integral part of a national political-economy’s structures, as bargaining includes wages, working rules, occupational health and safety standards, complaint procedures, employees’ status including promotions and other employment benefits. In this sense, a state labour law shall be regarded as basic element in a nation social system: the better are the workers’ conditions, the better is a social system, as employment “standards” reflect the level of “social guarantees” in a society. The government authorities are seeing that labour laws and bargaining contracts are enforced.

Se, for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_union

Thus, “bargaining” process is about “mediating” relationship between employees “united” in trade unions (all sort of workers, contractors and entrepreneurs), employers’ entities (employers, corporate and other business associations) and the government authorities; hence a collective labour law in some countries regulates, in part, the tripartite relationship among employees, employers and government bodies.

Government’s participation is not formal; on the contrary, it is an active part in “tripartite governments: e.g. governments actively support almost all social movements (for example, through a massive financial support in political parties’ membership). In the same way governments have to support labour movements: actually they do in the Nordic countries. That’s quite logic: e.g. without budget’s support labour movement will not be an effective part of national progressive growth.

Different outcomes can be envisaged after pandemic: mild, harsh and/or severe; however, recovery shall be adaptable to a specific national situation and corporate conditions in a certain country.

Labour unions’ issues in the EU

European trade union cooperation is mostly carried out within the European Trade Union Confederation, ETUC founded in 1973. EU’s decision making is important for workers, i.e. the unions must therefore keep track of the development of new initiatives and laws. In addition to the national arenas, the EU is an important political forum for the union movements; decisions made by the EU institutions impacted all unions in the EU-27. This aspect shows an important contemporary trend contrasting with a diminishing importance of national movements in some states and signifies new challenges for the unions’ work. It is important to mentions that most of the “employment” issues are within the shared competence between the states and the Union (TEU, art.2).

Increased business competition results in insecure employment and puts wages and other working conditions under pressure.

The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) is an EU advisory body comprising representatives of workers’ and employers’ organisations and other interest groups. It issues opinions on EU issues to the European Commission, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament, thus acting as a bridge between the EU’s decision-making institutions, workers and EU citizens. The EESC provides a “consultative support” to the EU’s drafts on three main issues: a) ensure that EU policy and law are geared to economic and social conditions, by seeking a consensus that serves the common good; b) promote a participatory EU by giving workers’ and employers’ organisations and other interest groups a voice and securing dialogue with them; and c) promote the values of European integration. Three groups are represented in EESC: employers, workers and other interest groups, so-called “diversity group” (e.g. farmers, consumers, etc.). Source:

https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/european-economic-social-committee_en

Most “advanced” labour union’s organisations have their representation in the EU’s headquarters in Brussels. Thus, the Brussels office of the Swedish Trade Unions was established in 1989; it is jointly run by the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), Swedish Confederation for Professional Employees (TCO) and Swedish Confederation of Professional Associations (Saco). These three organisations represent around 3.5 million Swedish workers. The main task of the Swedish office (composed of four civil servants) is to follow the EU’s integration efforts, in general and, particularly, to “influence” those aspects of the Union’s economic policies that are having consequences for workers’ interests. The office is visited by about 1500 guests every year. Source: https://www.fackligt.eu/swedish-trade-union/

National unions’ representations in Brussels gather information concerning EU legal drafts originating from the European Commission, as well as new laws adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of Minister. Important as well are the resolutions adopted by the main European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) concerning socio-economic progress, integration and labour market policy.

On the other hand, the “Brussels Offices” play important role linking together the national trade unions and the Union’s authorities. Besides, these offices supply vital “first-hand” information to national decision-makers, politicians, civil servants, researchers, etc. regarding European policies with effect for the trade unions. Additionally, these offices receive many visitors and draw programs for trade union groups that want to learn more about the EU.

https://www.lo.se/english/trade_unions_and_the_eu

The EU has already developed an extensive labour legislation; but numerous labour unions’ issues (at least officially) are excluded from the EU Treaties, e.g. matters concerning direct wage regulation (e.g. setting a minimum wage), the fairness of dismissals and collective bargaining. Almost all other unions’ issues are included in a series of directives, e.g. Working Time Directive guarantees 28 days of paid holiday, the Equality Framework Directive, which prohibits all forms of discrimination and the Collective Redundancies Directive, which requires that a proper notice shall be given with proper consultations on decisions about economic dismissals.

However, the European Court of Justice has during last decades extended the Treaties’ provisions via case law. For example, the trade unions have sought to organize across borders in the same way that multinational corporations have organized production globally; they sought to take collective action and strikes internationally.

This coordination was challenged in the EU in two controversial decisions. In Laval Ltd v Swedish Builders Union a group of Latvian workers were sent to a construction site in Sweden. The local union took industrial action to make Laval Ltd sign up to the local collective bargaining agreement. Under the Posted Workers Directive (art. 3) there are minimum standards for foreign workers so that they receive at least the minimum rights that they would have in their home country in case their place of work has lower minimum rights. The Directive says that this “shall not prevent application of terms and conditions of employment which are more favourable to workers”. For most people this would mean that more favourable conditions could be given rather than the minimum (e.g. Latvian) by the host state’s legislation or a collective agreement. However the European Court of Justice (ECJ) said that only the local state could raise standards beyond its minimum for foreign workers. Any attempt by the host state, or a collective agreement (unless the collective agreement is declared universal) would infringe the business’ freedom (TFEU, art.56). This decision was implicitly reversed by the ECJ and the Rome I Regulation, which made clear that the host state may allow more favourable standards.

However, in The Rosella, the ECJ held that a blockade by the International Transport Workers Federation against a business that was using an Estonianflag of convenience (i.e. it was operating under Estonian law to avoid taxation and labour rules in Finland) infringed the business’ right of free establishment under the EU law (TFEU, art. 49). The ECJ recognized the workers’ “right to strike” in accordance with the ILO Convention, but said that its use must be proportionately to the right of the business’ establishment.

More on EU labour law in: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labour_law

European Labour Authority, ELA

Over the last decade the number of mobile citizens (people living and/or working in another EU state) almost doubled and reached 17 million (2017). The ELA’s aim is to help individuals, businesses and national administrations to get advantages of the free movement and to ensure fair labour mobility. Thus, the ELA’s objectives are three-fold:

- provide information to citizens and businesson opportunities for jobs, apprenticeships, mobility schemes, recruitments and training, as well as guidanceon rights and obligations to live, work and/or operate in another EU state.

- support cooperation between national authorities in cross-border situations, by helping them ensure that the EU rules that protect and regulate mobility are easily and effectively followed.

- provide mediationand facilitate solutions in case of cross-border disputes, such as in the event of company restructuring involving several EU states.

Social dialogue in the EU

National-level bipartite social dialogue and collective bargaining is at the heart of the EU’s industrial relations with an appropriate support the principle of subsidiarity and the autonomy of the social partners. Structural gaps at national level include lack of representativeness and mandate to negotiate, limited “tripartism”, sectoral collective bargaining and low collective bargaining coverage, lack of social partners’ autonomy and lack of trust between the social partners and governments.

Elements that would foster a more effective social dialogue at national level include legislative reforms to promote social dialogue and collective bargaining, a more supportive role by the state, increase in membership, capacity and mandate to negotiate, more human and financial resources.

Developing the skills and expertise of the two sides of industry in relation to specific skills (such as industrial relations, negotiation, research and analysis, policymaking, advocacy, and soft and digital skills) should be supported. Social partners should be assisted in their efforts to increase their membership representativeness and capacity to negotiate and implement agreements.

Source: Eurofound (2020), Capacity building for effective social dialogue in the European Union, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Trade unions in Nordic countries

Focal point in the Nordic model is that at a national level, trade unions negotiate collective agreements/bargaining with employers’ organisations and the state’s authorities, i.e. so-called “tri-party” agreements; though it’s voluntary for the companies to adhere to the “agreement”. Since collective agreements regulate large parts of the labour market regulation, the trade unions play an important role to secure decent wages and working conditions. The regulation of working conditions is primarily in the hands of the social partners, contributing to the creation of a dynamic labour market and at the same time strengthening the influence and relevance of the social partners.

The “union’s” problems have direct effect on workers: thus, only in Denmark about 600 thousand employees in private labour market are involved; existing system in some Nordic states doesn’t take so far the individual interests in the tripartite bargaining (among business, unions and government). Recent analysis has shown that about 43 percent of workers in private sector would rather make “individual arrangements” than go through collective bargaining. For example, in Denmark there is no legislation regulating wages: they are defined exclusively in the collective agreements; then further on the wage setting and the development of salaries are negotiated at company or sector level.

https://www.workindenmark.dk/Working-in-DK/Trade-unions

Presently, the Nordic countries are having the highest rates on union membership in Europe and, probably, in the world. Thus, some recent statistics has shown that the percentage of workers belonging to a union (so-called, labour union density) was over 90 percent in Iceland, about 66-67 percent in Denmark and Sweden (excluding students working part-time, the Swedish density could reach 68 percent), followed by Finland with 64 percent and Norway with about 52 percent.

In all the Nordic countries with a Ghent system (see below): in Sweden, Denmark and Finland the union’s density is about 70 percent. Considerably high membership fees of Swedish union unemployment funds implemented by the new center-right government in January 2007 caused a certain drop in membership in both unemployment funds and trade unions: during 2006-08, the union’s density slightly declined from 77 to about 70 percent. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_union#Nordic_countries

Note: By the Ghent system is understood in some states an arrangement in which the main responsibility for welfare payments, especially unemployment benefits, is held by trade/labor unions, rather than a government agency. The system is named after the city of Ghent in Belgium, where it was first implemented. It is the predominant form of unemployment benefit in Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Sweden. Belgium has a hybrid or “quasi-Ghent” system, in which the government also plays a significant role in distributing benefits. In Nordic states, unemployment funds are managed by unions/labour federations and/or partly subsidized by governments. As soon as workers in many cases have to belong to a union to receive benefits, union membership is higher in countries with the Ghent system. Furthermore, the state benefit is a fixed sum, but the benefits from unemployment funds depend on previous earnings. More in: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghent_system

Box: Nordic states’ labour market statistics

= two-thirds of Nordic women are full-time employed;

= employed by gender: 54 percent men and 48 percent women;

= general unemployment rates in the region –about 6 percent and among youth – about 17 per cent (before the pandemic);

= annual median income: single person with dependent children – €15-20.000; two or more adults with dependent children – € 22-27.000.

Note: there are eight countries in the Nordic region – Denmark, Faroe Islands, Greenland, Finland, Aaland, Island, Norway and Sweden. Source: www.norden.org/facts

Denmark

The Danish model is based on the collective representation of the employees rather than on giving the individual employee rights. Although workers are free to join a union, it is in fact the union with its “collective strength” that protects the employees’ rights, not the individual employee; hence about 70 percent of the Danish workforce is attached a certain trade union, the highest figure in the Nordic states. Most union members are associated with the main labour confederation (so-called FH, as a result of a merger in 2019) and with the Akademikerne-union; the latter unites all occupational and educational workers; however, there are several labour unions outside these two main confederations.

The membership of a specific union is not an obligation for a worker; generally, the choosing of a union depends on education/position and or a workplace. Trade unions are associated with unemployment insurance funds; it provides an incentive to join a union. More in: https://www.workindenmark.dk/Working-in-DK/Employment-contract

A diversified union’s system in Denmark consists of the following unions:

= Central, so-called “united” unions’ organisation, FH with about 1,3 mln members and 65 sub-organisations. More in: In: https://fho.dk/om-fagbevaegelsens-hovedorganisation/hvad-er-fh/hvem-er-fhs-medlemmer/

= Danish Confederation of Professional Associations (AC “Akademikerne”, founded in 1972): it is an umbrella organisation for numerous organisations “united” under the AC structure. The members of the AC-associations offer services to professional and managerial staff graduated from universities and other higher educational institutions.

Source: https://www.akademikerne.dk/events/vaekst-og-beskaeftigelseskonferencen-2020/

= Professional and/students association/union (with 97 thousand members) in social sciences, economy, business and law, called Djøf; the union accepts as members both already employed in private and public sectors or looking for a job. E.g. about 22.000 students are already members of Djøf. They have such advantages as favorable insurance, free-digital courses in Excel, Photoshop, etc. Often the unions provide new members with one year-free-fee’s membership plus about 50 euros for textbooks; after a year, their membership fees are about 49 DKK or about 6,5 euro/month; otherwise the fees varied from about 450 to 900 DKK or 60-110 euro/ per quarter. Source: https://www.djoef.dk/omdjoef/hvem-er-dj-oe-f.aspx and https://www.djoef.dk/english.aspx

= Danish Society of Engineers, IDA, is a professional organization with more than 125,000 members working and studying in the fields of technology, natural sciences and IT.

More in: https://ida.dk/

= Trade union of workers in the financial sectors; More in: https://www.finansforbundet.dk/en/

Sweden

The level of union membership in Sweden is at the general “Nordic level” at about 70 percent; it has fallen from its peak of 86 percent in 1995. There are three main union confederations: LO, TCO and Saco, which are divided along occupational and educational lines in which Swedish employees are grouped; a strong and Swedish Trade Union Confederation, LO unites 14 big trade unions. Many employees’ issues: e.g. working hours, minimum wage and right to overtime compensation are regulated through collective bargaining agreements in accordance with the Swedish model of self-regulation, i.e. regulation by the labour market parties themselves in contrast to state regulation and labour laws.

Swedish labour legislation represent a comprehensive code of statutes which include, inter alia, the Annual Leave Act, the Promotion of Employment Act, the Co-determination Act, the Work Environment Act and the Working Hours Act. More in: https://www.lo.se/english/labour_legislation

Specific part of labour force in Sweden is a political cooperation between LO and the Social Democratic Party as both reflects the same set of values. In modern society, the union-political cooperation constitutes a major tool in influencing decision-making. However, LO has other means to exert influence in the society, including contacts with various organisations, authorities and political representatives. Exerting contacts between trade unions and political parties regarded as complementary representing two different ways of reaching the same policy goals.

https://www.lo.se/english/political_cooperation

Basic aspects of Swedish labour law and collective agreement/bargaining involve some procedural rules on the right to negotiate and basic rights for workers: most of it is in the “Co-Determination Act” and “Employment Protection Act”. Main aspects of individual labour rights and obligations are formulated in collective agreements, e.g. without a statutory minimum wage it is the latter that stipulates how wages should be paid at all; thus, collective agreements and individual contracts are the only ways to define how a worker is paid for the work performed. Without agreement, an employer can pay any level of wage as long as the employee accepts it.

Swedish collective bargaining model is based on a strong cooperation between the union and employers’ organisation: about 80-90 per cent of workers in Sweden are protected by collective agreements. A high level of “unionization”, together with the absence of legal restrictions in unions’ activities, stipulates that “social partners” play a vital role in collective agreements.

There are over a hundred national contracting parties in the Swedish labour market, covering over 650 collective agreements at national level.

The social insurance system is administered by two government agencies: Swedish Social Insurance Agency and/or Swedish Pensions Agency; collective insurance schemes and occupational pension schemes are regulated in collective agreements between employer and employee organizations at the national level. Generally, employees are entitled to benefits under these schemes if: their employer is a member of an employer organization, which means that the collective agreement is automatically applicable; or if an employer concludes an agreement with the relevant trade union. The premiums for negotiated insurance and occupational pension schemes are paid by the employer out of the negotiated pay settlement. In other words, some of the employees’ pay is used to fund the insurance scheme instead of being paid out in the form of wages. Collective insurance and occupational pension schemes are normally administered by an insurance company that is jointly owned by the social partners. More in: https://www.lo.se/english/facts_and_figures

Finland

The main purpose of a union is to safeguard and improve the benefits and rights of its members; it includes, e.g. wages, employment security, quality of working life, etc. Generally, Finnish unions are so-called “occupation-based” with the three main levels: local trade unions, national federations and labour confederations which are made up of affiliated federations. Collective agreements covering the whole of Finland are concluded among the federations.

There are over 2.2 million trade union members in Finland, including working people, retired, unemployed and students; around a quarter of union members are not working while a very large proportion of employees are the union members. Statistics Finland noticed that the union’s density was 73 percent in 2008, equivalent to almost 1.6 million union members; presently, this figure reduced to about 69 percent.

https://www.expat-finland.com/employment/unions.html

There are three trade union confederations in Finland: the biggest (SAK) with over one million members (2019) organises manual workers, although around one-third of its members are non-manual. STTK is the second union with 608 thousand members (2019); it organises graduate employees and non-manual workers. The third largest union confederation is AKAVA with about 589 thousand members: it organises graduate employees and also non-manual workers. These three confederations work closely together: a co-operation agreement between was concluded already in 1978. There is, however, some competition between STTK and AKAVA for graduate employees, with AKAVA showing greater growth; a number of smaller unions, including the 11,000 strong police union, switched their affiliation from STTK to AKAVA during the ultimately unsuccessful merger discussions in 2015/16. https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Finland/Trade-Unions

SAK has 2218 affiliated smaller unions, primarily organised on an industry basis. The largest SAK affiliate is PAM, which represents workers in the private services sector and has about 231 thousand members. The next largest is Teollisuusliitto (Industry union), created out of a merger between the metal workers’ union, the industry union TEAM and the woodworkers’ union in January 2018, with 211,995 members.

AKAVA with 35 affiliates is organised professionally: its largest part is OAJ representing about 121thousand teachers; the second largest, TEK with 72 thousand members, organises graduate engineers; the third largest IL with 70,8 thousand organises professional engineers (all figures for January 2015).

The unions’ density has been generally stable during a recent decade at the level of 73 per cent; one reason for the high figures is that unemployment insurance is typically obtained through union membership, although it is also possible to be insured through an unemployment fund without being a union member. However, in 2019 the unions’ density had fallen from 64,5 to 59,4 percent.

Unions increasingly recognise that they need to take active steps to recruit those joining the labour market if they are to maintain their strength and influence; young people are a particular target, and the unions encourage students to join. For example, AKAVA is presently a confederation with the largest proportion of students as members with more than a hundred thousand students (united in a special student council AOVA). AKAVA’s membership has increased sharply in recent years, going from 375,000 in 2000 to about 600 thousand presently.

Reference to: L. Fulton (2020) National Industrial Relations. -Labour Research Department and ETUI. Online publication at: http://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations.

Norway

More than half of Norway’s employees are in unions; although the union density has declined slightly in recent years. The majority of unions are grouped in four confederations: LO, UNIO, YS and Akademikerne. While UNIO and Akademikerne primarily organise more highly qualified employees, there is direct membership competition between LO and YS unions.

Affiliated trade unions are, in turn, centrally organised through a main organisation or main confederation. In Norway there are four such confederations:

= Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions LO is Norway’s largest workers’ association with 22 different professional unions affiliated with LO, including employees in Norwegian Union of Commerce and Offices Employees, the Electricians and IT Workers Union, and the union for workers in industry and energy sectors; these unions organise members in the municipal, county council and private sectors.

= Confederation of Unions for Professionals is Norway’s second largest employee organisation, which unites the Norwegian Nurses Organisation, the Education Union, the Norwegian Police Federation and the Norwegian Physiotherapist Association.

= Confederation of Vocational Unions, YS with 19 affiliated unions, covering workers in several sectors, incl. professional drivers, librarians, teachers and the pharmacists’ unions.

= Federation of Norwegian Professional Associations is an employee organisation for professionals with higher university’s qualifications and colleges; it consists of 13 member associations, which include the union for architects, Norwegian medical association, Norwegian dental association and the Association of social scientists.

Source: https://www.norden.org/en/info-norden/trade-unions-norway

Germany

Collective bargaining coverage in the country is about 62 percent; in the industrial sectors cooperation among trade unions and employers’ organisations is still the most important mechanisms for setting wages and working conditions in Germany. However, the system is under pressure as employers leave professional employers’ organisations, and that the present agreements provide for greater flexibility at company level.

Only around a sixth of employees in Germany are union members, although the decline in union density has slowed in recent years. The vast majority of union members are in the main union confederation, the DGB; however, individual unions, like IG Metall and Ver.di, have considerable autonomy and influence.

Workers’ councils provide representation for employees at the workplace and they have substantial powers: e.g. extending to an effective right of veto on some issues. Source: https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Germany

The Baltic States

Historically, during last fifty years, the labour unions in the Baltic States have formed a part of the Soviet Union’s trade union system being closely connected with the party’s organisation in the state; hence the industrial relations were not a part of the unions’ activities. After 1990s trade unions in the Baltics have experienced rapid loss of membership; at the same time, employers’ organisations increased their influence and membership. Low financial and organizational capacity caused by declining membership added to the problems of union’s “interests”, as well as workers’ protection in negotiations with employers’ and state organisations.

Differences still exist among the Baltic States in the ways the labour unions are organised, in the unions’ density and functions; thus, starting from 2008 the union density have been decreasing in Latvia and Lithuania, while in Estonia the density’s indicators are even lower than that of Latvia and Lithuania with about 7 percent of the total employment. Historical legitimacy is one of the negative factors that define a low level of labour unions’ collective powers.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_union#Baltic_states

= Latvia: the LBAS is the main trade union confederation in Latvia; almost all existing unions belong to it. Union density is low – at about 12 percent- but higher than in other two Baltic States; much higher share of membership is recorded in the public than in the private sectors. Collective bargaining system covers 34 percent of workers. Employee representation at the workplace is either through unions or through elected workplace representatives. However, with low levels of union membership, particularly in the private sector, and reluctance among employees to elect workplace representatives, most workplaces have no employee representation at all. Source: https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Latvia

= Estonia: the union’s density in Estonia is the lowest in the Baltics at 7 percent; most union members are organised in two major confederations: a) EAKL for primarily manual workers, and b) TALO, for generally non-manual workers; collective bargaining system covers 33 percent of workers.

https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Estonia

= Lithuania: the union’s membership is quite low- at about 9 percent of all employees. The unions are divided (mainly, on ideological grounds) into three main confederations: LPSK, LDF and Solidarumas; recently, the unions were showing a trend for more cooperation.

Collective bargaining system covers 15 percent of workers; since 2004 elected works councils have had bargaining rights in cases with no unions’ organisation present; however, that doesn’t increase the bargaining’s importance. Lithuanian legislation now provides for employees at workplace level to be represented by a company-level trade union, by an external union, to which they have transferred their representational rights, or by a works council.

Both company-level unions and works councils have almost identical functions, including collective bargaining and information and consultation, and since 2005, works councils can also organise strikes; practically, there are no unions or councils at most workplaces in Lithuania.

https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Lithuania

= Poland: trade union density is relatively low at around 12 percent of employees and membership is mainly divided between two large confederations: NSZZ Solidarność and OPZZ, followed by a somewhat smaller one, FZZ. Significant number of union members is still in small local unions not affiliated to any of the main confederations.

Only a few employees in Poland are covered by collective bargaining – about 10-15 percent, which takes place largely at company or workplace level. This means that where there are no unions to take up the issue, payment and working conditions are set unilaterally by employers subject to the national minimum wage.

Polish legislation provides for employee representatives at supervisory board level in state-owned and privatised enterprises; even greater powers belong to some state-owned enterprises. There is no right to employee representatives on the boards of private companies.

https://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Poland

Challenges

Labour/trade-union membership dropped sharply in the EU and globally during last decade, falling to about 20 per cent of workers in 48 out of 92 countries, according to International Labour Organisation, ILO in the latest annual report: World Labour Report 1997-98. The ILO says that in 1995, roughly 164 million of the world’s workforce of 1.3 billion belonged to trade unions; in 14 out of 92 countries surveyed the union membership rate exceed 50 per cent of the national workforce. In all but about 20 countries, membership levels declined during the last decade. According to ILO, in spite of the negative trends, the drop in union numbers has not resulted in a corresponding drop in influence: in most countries, trade unions managed to consolidate their strength and develop new collective bargaining strategies.

Trade unions’ membership in Europe is on a positive side: about 7,5 mln members in Northern Europe, about 23,8 mln in Western Europe, some 10 mln in Southern Europe, and about 14 mln in Central and Eastern European states (out of total 164 mln in the world).

Source: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_008032

Re-elected ILO Director-General, Guy Ryder recently underlined that although many observers saw only decline, the real picture showed increased democracy, greater pragmatism and freedom for millions of workers to form representative organizations. Dramatic rise or fall of trade union membership is usually linked to systemic changes in governance or major legislative overhauls in many countries and regions. For example, the drop in union membership was sharpest in central and eastern European countries, which saw an average decline of almost 36 per cent, much of which resulted from the ending of quasi-obligatory union membership following the breakup of the former Soviet bloc. Unionization rates in Estonia were down 71 per cent, in the Czech Republic by 50 per cent, in Poland by 45 per cent, in Slovakia 40 per cent and Hungary by 38 percent. Much of the decline in Germany’s unionization rate (20 per cent versus 16 per cent average in the EU) is attributable to the drop in former East Germany. But not only in Europe, the union membership in the US declined by over 21 percent during the last decade, turning the country towards one of the lowest levels of unionization among industrialized countries.

Source: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_008032

While unions in most countries have moved “towards a less adversarial and more cooperative” approach, trade unions have shown themselves capable of wielding power in times of crisis. In a number of recent industrial and political conflicts (France and Germany), labour unions proved decisive in reaching settlements. Innovative social structures, such as the implementation of works councils in Europe and various “social pacts” (along the lines of those implemented in Ireland and Italy which have boosted growth, restrained inflation and reduced unemployment) owe much of their inspiration to trade unions. Large numbers of new entrants to the labour market are not being unionized and that the relative numerical importance of unionized labour is decreasing as a percentage of the workforce in most countries. The number of unionized workers remained steady in Italy, but the percentage of unionized workers in the labour force decreased by 7 percent to 44 percent of the total since the mid-1980s.

Labour unions are going to be important as a vital economic factor during green and digital transition in Europe as “vehicles of democracy and advocates of social justice”. Therefore, quite notable are the points of the EU’s agenda for new skills and jobs, which is meant to create conditions for modernising labour markets, elaborating strategies for raising employment levels, and ensuring sustainability of the EU social models.

Business and entrepreneurship: tackling post-pandemic challenges

During the post-pandemic period, corporate entities and employers in general have been trying to adapt to new and unexpected challenges while figuring out the perspective development strategies. There are two elements affecting business by corona-virus’ pandemic stemming: a) from external factors, such as changes in global, regional and national political economy, and b) from internal factors, which include changes in the corporate policies and dynamics inspired by adjusting to diversified consumers’ preferences and other factors affected by the pandemic.

Among the main facets in drafting the survival approaches, businesses have been trying to tackle two main issues: retaining the employees and implementing digital facilities; both would last for perspective strategies while dealing with the pandemic’s negative effects.

Among the changes in the corporate internal structures, while remaining agile, the companies are going tom be increasingly sensitive in corporate social responsibility, as well as in business technology, green and digital transition issues.

Note. Within the Institute’s “post-Covid” research project, its first part has already covered the workforce and labour relations’ issues affected by the pandemic: references to the following links:

– https://www.integrin.dk/2020/10/07/workforce-after-pandemic-the-process-of-continuous-reforms/, and

– https://www.integrin.dk/2020/10/09/labour-movement-in-european-integration-facing-modern-challenges/.

The present article covers the second aspect in the “post-covid” research concentrating on some corporate and entrepreneurship issues in modern political economy affected by the “post-Covid” implications.

More on the EII’s project in: https://www.integrin.dk/post-covids/

Introduction

As it has become important in the post-pandemic time, the companies and entrepreneurship in general, have been taking into consideration contemporary challenges which were already changing peoples’ life styles and habits, as well as the consumption patterns; the latter were becoming vital for corporate strategies. Ever greater modifications occurring in consumers’ behavior are already turning the corporate strategies towards models which are more prepared for continuously changing consumers’ preferences and “tastes” guiding corporate activity.

For any business it is vital to understanding the main “features” that are driving consumers choices and “shopping instincts”: these are the key factors which businesses need to consider when formulating strategic approaches. Several key consumer types have been explored recently, stretching from lifestyle choices, buying habits and business-to-consumers interrelations, etc.

More in: Westbrook G. and Angus A. – Euromonitor International: Top 10 Global Consumer Trends 2020, in: http://go.euromonitor.com/rs/805-KOK-719/images/.

Transforming political economy, transforming business

In the EU integration, it is the Treaties that define the “general sketch” of the EU-member states’ economic coordination: the EU basic law also regulates the main political economy’s principles. Thus, the Lisbon Treaty (in effect from the end of 2009) has formulated some guiding principles in economic policy, which include:

– First, European internal market and integration as the background of the EU economic policy;

– Second, the EU’s sustainable development based on the member states’ balanced economic growth and price stability;

– Third, a competitive social market economy, aimed at full employment and social progress;

– Fourth, high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment;

– Fifth, promotion of scientific and technological advance; and