Views: 56

The EII’s research on the role of European integration in modern global governance is aimed at analysis of changes and transformations in the structure of global governing structures and in national political economies. New approaches to national development and growth patterns through new patterns in geo-politics and geo-economies are seriously affecting both the theory and practice of global governance and the EU integration model. Alongside the global “transitional components”, like digitalisation, sustainability and climate change efforts, some new patterns impacted the EU perspective growth.

The EII team is introducing a new Institute’s research block with a new EII’s rubric “EU in the global governance, supplied with three inspiring articles which analyse modern multi-nationalism, the new world order and the EU’s role in the globalisation process, i.e. the issues reflecting changes in contemporary international relations and global governance.

The EII’s research publication is composed of three articles: a) modern multilateralism: anatomy of contemporary global governance (I), b) modern governance: expected “reset” in international institutional framework (II), and c) the EU’s role, competence and importance in the modern multilateral global system (III).

Thus, the EII’s readers are invited to visit a new rubric in the list of the EII’s themes –“EU in global governance”.

Global challenges and national impetus

Generally accepted global challenges include some most important facets which a modern governance has to deal with, according to the following “global priorities” in the nature of the western-led international system:

= First in line, would be science and technology transformations: technological advances will have major impacts on socio-economic development with automation and machine learning having a dual effect on employment (i.e. with the potential disruption in job markets, making millions of jobs obsolete). Growing technological proliferation will force national governance to adapt the new forms of political economies for progressive growth.

= Second, climate change and resources’ policies: the consequences of climate change become increasingly apparent and climate-related political disputes will proliferate at the national and international level. Sustainability issues and renewable energy will be most cost-competitive issues in geo-politics. Climate change will be felt over the course of decades and will increase the likelihood of relatively sudden disasters (e.g. stronger hurricanes, extensive rains, heat and droughts).

= Third, appearance of new areas of states’ competition: in the geo-politics’ long-term trends it is important to consider the possibility of major conflicts centered on issues stemming from national economic interests. During next couple of decades they might include e.g. competition in space exploration, in new weaponry systems (e.g. drones and unmanned vehicles), cyber warfare and internet governance, Arctic Oceans’ exploration, etc.

= Fourth, the issues of digital economy/society which are becoming truly global.

= Finally, ageing population is due to lead to a combination of increased life expectancy and declining fertility rates. Although an increase in the pension age would reduce expenditures, the decision is difficult politically: such adjustments need a “social adaptation” to a gradual rising of the retirement age; e.g. the retirement age in Australia this has been raised to age 75 to match increased life expectancy (similar measures are expected in Sweden and Denmark in 2025.

Generally, world states’ economic progress and “political weights” is calculated by the GDP rates and figures; although quite often the GDP-estimates are regarded as obsolete, some other socio-economic parameters are taken into account as more accurate and feasible, like wellbeing, happiness, per capita share of growth, etc. Besides, countries are being “sorted-out” by numerous global financial institutions by a country’s “market value” and official exchange rates. However, nominal GDP does not take into account differences in the cost of living in various countries; situations and results can vary greatly from one country to another, and from year-to-year based on fluctuations in the exchange rates of the country’s currency (there are about 30 so-called “main currencies” in the world). Such fluctuations may change a country’s ranking from one year to the next, even though they often make little or no difference in the standard of living of its population. A more services-oriented economy will have different requirements for geo-economics, though three economic powers (the US, Europe and China) will remain the key decision-makers in global economic affairs.

The US is the world’s largest economy with a GDP of about $19 trillion (by the World Bank and the UN accounts), due to high average incomes, large population, capital investment, moderate unemployment, high consumer spending, relatively young population and technological innovation. At the same time, Tuvalu is the world’s smallest national economy with a GDP of about $32 million with a very small population, lack of natural resources, reliance on foreign aid, negligible capital investment, demographic problems, and low average incomes.

Anatomy of global geo-politics

Global governance is driven by numerous global institutions, both officially established (like the UN, World Bank and IMF, etc.), semi-official and private ones. Geopolitics in international relations deals with analysis of the states’ foreign policies in order to understand and predicts global political trends and perspectives. Among the main issues are – availability of natural resources, climate change efforts, sustainability policies, demography, etc. Besides, the geo-politics includes regional and geographical variables in connection with diplomatic history and relations, as it includes relations among international political actors’ interests focused on great powers. Therefore, geo-politics is closely connected to geo-economic: e.g. global aspects in sustainable/renewed energy policy have been turned into the practical implications in the global energy development and transitional national energy policies. Several other global challenges have turned traditional “international political relations” (e.g. political geography and others) into the geo-economic concepts. More in: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geopolitics

Rising nationalism has been a by-product of the wide-spread globalization’s process: growing and unregulated globalisation in political and economic sense after the end of “cold war” (it is really quite difficult “to regulate free trade” in a borderless world) produced unexpected outcomes. Most vital have been moving production to “more favorable states/regions” with a consequential unemployment to follow. During about last three decades the US has almost lost all its fundamental industries except some manufacturing sectors and, as a result, one in five American workers has been out of work. No doubt, the mottos like “America-first” and “Protecting American jobs” gained political strength and paved the way to seemingly “unexpected” president D. Trump’s victorious elections.

All that gave rise to “state capitalism” approaches in numerous old and emerging economies: e.g. in China the take-off in economy started when the state allowed a greater role for private companies. The ideas of a “bigger government” sounded good to the Nordic economic model with greater public sector than in many other countries around the world.

It seems that global elites (if one can stick to the idea of “global governance”), are now divided into two possible ways of “thought”. On one side, intellectually, the states are convinced of the need to keep markets open with free flow of trade and investment. On another side, politically, they are under pressure to “respond” to local electorate: voters generally are angry, frightened and demand urgent protective actions. In the latter, citizens are likely to take “practical priority” over abstract political ideas.

Recent events and developments in global economy have shown that globalisation had created an economic system which was more complex –and even more dangerous – than the initial euphoric ideas had ever imagined. For example, so far global elites have shown their inability to streamline global growth and entrepreneurship against a dangerous drift towards protectionism and growing nationalism: both could form the next stage in demolition of progressive global order. In fact, it’s difficult to convince local politicians about “priorities” in international business order, open marker and global integration (presently called globalisation); although politicians have to listen to electorates… International trade and investment is generally falling and protectionist barriers are on the rise. Economies are more oriented towards gaining from exports at all costs: globalisation ideas are still in the discussion clubs’ agenda, but practical events often move the opposite direction. Hence, the decisions at world trade talks are being so often broken: politicians raise their voices in favor of globalisation at global meetings but often take contradictory steps back home.

Contemporary analysis of global trends to 2035 in the geo-politics and geo-economic started at the end of 2017: the research was written by the Oxford Analytica at the request of the Global Trends Unit of the Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value (in the Directorate General for Parliamentary Research Services, DG EPRS) of the General Secretariat of the European Parliament. It considered eight economic, societal, and political global trends that would shape the world to 2035, namely: ageing population, fragile globalisation, technological revolution, climate change, shifting power relations, new areas of state competition, politics of the information age and ecological threats. It examined the effects of these challenges in the geo-politics and economic while considering four scenarios based on two factors: an unstable or stable Europe and world presenting the EU’s policy options and trends in addressing these challenges.

Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_STU%282017%29603263. The study’s reference: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/603263/EPRS_STU(2017)603263_EN.pdf. Besides, more information on geo-politics and environmentalism, in: https://democracyjournal.org/magazine/14/geo-politics/, By Edward Gresser.- Fall, 2009.

Global and regional “geo-economics”

Global GDP was calculated at the last year before the Covid-pandemic (i.e. the end of 2018) at about $80 trillion (though, according to the World Bank’s data, it was little less $75,5 trillion. The countries/regional blocks’ share (in trillions $, so-called “trillion’s club”) – about 20 in total- have been the following: the US – 19,4; the EU-27 – 17,3; China – 12; Japan –about 5; Germany -3,7; Mercosur’s bloc -2,8; the UK -2,7; India and France -2,6 each; Brazil – 2; Italy – 1,9; Eurasian Economic Union – 1,8; Canada- 1,6; South Korea and Russia – 1,5 each; Gulf Cooperation Council’s states -1.4; Australia -1,4; Spain -1,3; Mexico -1,1; and Indonesia -1,0.

Other “global economic powers” are having GDPs at the level less than a $ trillion: e.g. Turkey –about $850 million, Netherlands – $826, Saudi Arabia – $684 and Switzerland –about $678 million USD.

The global GDP rates fluctuated in the last 35 years at 2-4 percent (with annual growth by 6-7 percent), exports as percentage of GDP grew in the EU from about 22 percent to about 45 percent during the same period, and in the world from 16 to 30 percent.

In some Baltic Sea region’s states the GDP rates are the following (in the US$): Denmark – about 330-350 billion (35-36 global rank); Poland -525 billion (23-24 rank); Sweden – about 520-540 billion (22 rank); Norway – about 371-400 billion (29 rank) and Finland – about 240-253 billion (44 rank). Among the three Baltic States: LT- 47 bn (86 rank), LV- 30bn (99 rank) and EE- 26 bn (103 rank).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)

Note: Estimates compiled by the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook. In:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Economic_Outlook -April 2018; for comparison, one can see some MNC’s capitalization, shown below, which are often bigger than some states’ GDPs.

It is important to mention, that on a global scene the politics and economic are more integrated than, for example on the states’ level; in particular, there are some “regional blocks” that are gaining importance; generally they include the G-7 and G-20 groups, the European Union, which is uniting in socio-economic integration 27 states with $17,3 trillion GDP; Mercosur, as an economic union of the states located in South America (including Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay with about $ 2,3 trillion GDP); Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), as an economic union of 5 member states that are included some former Soviet Union’s republics (i.e. Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan); Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), as an economic union of 6 member states that are located in the Arabian peninsula, i.e. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain, and several other blocks.

Thus, there are influential sub-regional politico-economic partnerships for example, in the far-east (which includes nine Asean member states as well as China, India, Japan and New Zealand) and twelve former trans-pacific partnership states.

Although it is generally accepted that globalisation and free trade are “jolly good things”, it has been for long the US and European states which “shaped” the progress in globalisation. Informally, however, it was accepted that “the flow of ideas” (as well as investment, funds, jobs, work force, etc.) have been moving from west to east. In fact, presently it is nations in Asia, Latin America, Africa and other so-called “emerging economies” have been most comfortable with the present stage of globalisation. Therefore the leaders in these countries are for the globalisation process to proceed and even supporting western states to go on with the “global free trade”.

Some figures in the web-link below clarify the point: there are, for example, the IMF’s calculations for developing countries and emerging economies (so-called, DC&EC); however, the data are from a period before the COVID-pandemic, the growth rates globally are impressive: – 4,9% (and generally in western countries -3,7%); with the GDP per capita in about -$5,5 thousand; DC&EC’s share in the world has been about 60%.

More in: http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD and

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2018/03/20/world-economic-outlook-april-2018. See also information from the “global growth consultancy” at: http://gdpglobal.com/.

Lessons from the Nato-allies’ Afghan-retreat

There are certain geo-political lessons from a recent “allied forces” withdrawal from Afghanistan. From an economic perspective, the EU has few carrots to use against the Taliban regime, as the block’s share in trade with the country hardly reached two percent during last decade; the Afghan’s traders generally turn to eastern states, like Pakistan, Iran, China and India for economic relations. However, Afghanistan benefits from the EU’s “everything but arms” preferential treatment scheme, which means Afghan traders have access to the EU market tariff-free for 75.9 percent of goods. Around 30 percent of Afghan exports to the EU use this program. But if Brussels was to cut it, it’s likely to have a small impact on the country’s overall economy.

Global development aid has a certain bargaining chip: e.g. EU’s generous help in financing development programs for Afghanistan reached €1.4 billion during 2014-2020; as to Belarus, the EU could cut off all direct aid for state-related entities.

However, although China is ready to deepen “friendly and cooperative” relations with Afghanistan, the country poses a dilemma: China needs a stable Afghanistan (the US withdrawal followed by the Taliban’s rise was not Beijing’s preference); but from an ideological “domestic point”, China is worried to support Taliban in relation to its own control over its Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang (in this regard, the US has set a “trap” for China with its troop withdrawal. On the other hand, sensing the unavoidable geopolitical reality, the Chinese government made significant diplomatic steps toward the Taliban’s leadership, and the Taliban in turn promised not to hurt any Chinese on Afghan territory; it all creates conditions for China to keep up and even boost its economic ties with Afghanistan.

As to “real geo-politics”, the US military mission in Afghanistan, the US President acknowledged, was never supposed to be nation-building nor creating a unified and centralized democracy: the only vital national interest in Afghanistan remain, i.e. preventing a terrorist attack on American homeland. However, a withdrawal has underlined the gap between the American global aims and its ability to achieve them. Presently, 18 million people, or about half of Afghanistan’s population, need humanitarian assistance; but for Afghans desperate to escape the Taliban, the EU-27 has had a mixed message: the German Christian Democracy party argued that Germany can take in everyone in need; the focus must be on humanitarian aid on site, unlike in 2015 (not quite Merkel’s “We can do it all.” The Greece government has had a similar message: the country didn’t want a repeat of 2015, when nearly a million people crossed its borders before moving to the rest of Europe.

The US President’s decision to allow Afghanistan to collapse into the arms of the Taliban has made European and other allied-forces’ officials worried about the perspectives of the Western alliance and everything it is supposed to stand for. Besides, the NATO’s allies have left in Afghanistan substantial military equipment – on different accounts the following stuff has been left behind: about 700 thousand weaponry and ammunition, 30 thousand military vehicles and about 170 military airplanes and helicopters! Besides, combating terror has been an expensive endeavor: only in the US, the bill has been about $300 million/per day during 20 years, or about 20 trillion –i.e. one fourth of yearly global wealth…

Other global challenges

= Global information network. Some 300 years ago, the initial principles of democracy made people independent, Google, Facebook and Twitter, to name a few, are creating a sort of global information monopoly. Thus Google has 88% market in the US and about 90% in Europe; Facebook increased its share of influence with WhatsApp, Messenger and Instagram: in the US Facebook controls about 75% of social media in mobile network. “Tech-giants” are increasing their power by free-flow of advertising platforms; traditional media are forced to follow the lead… Ten biggest multinationals, MNCs capitalization (in billion $, mid-2016) looks the following way: Apple –over 520, Google -480, Microsoft – about 400, Exxon Mobil – 330, Berkshire Hathaway* – over 310 (488 –in 2017, and in 2018 –about 300), Facebook –over 290, Johnson & Johnson**) – over 280 (284 in 2017), General Electric -260, Amazon -237 and Nestlé+) – over 235 (in 2017 -244 CHF). All figures can slightly change from year-to-year’s account.

Note: nine of the ten are actually American companies, though four –in ICT sector- are relatively young!

*) Berkshire Hathaway is a holding company for a multitude of businesses, run by a famous Chairman and CEO, Warren Buffett. See: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/berkshire-hathaway.asp?partner=asksa.

**) over 130 years in business –mainly health, medical devices, pharmaceuticals & wellness, e.g. baby care. Alex Gorsky, CEO.

+) world’s largest food and beverage company has a motto “Good food, good life”. https://www.nestleusa.com/ . So one can pose a choking and vital question: what’s the use of G-7/G-20 summits if 10 global MNCs can really influence the state of world population’s interests and wellbeing?

Already over 55% people in Denmark, for example, get their news from Facebook; all other news sectors have to play for internet’s rules. Connections to customers and getting their “attention” is becoming more important that “physical goods”: hence ICT-companies for long have overrun energy and oil companies. Digital market has been greatly commercialized with increasing conquering of public/customers’ attention.

= Cyber security: The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence is a NATO-accredited cyber defence hub focusing on research, training and exercises. The international military organisation based in Estonia currently includes 21 nations providing a 360-degree look at cyber defence, with expertise in the areas of technology, strategy, operations and law.

More in: www.ccdcoe.org.

= China’s latest intentions in geo-politics

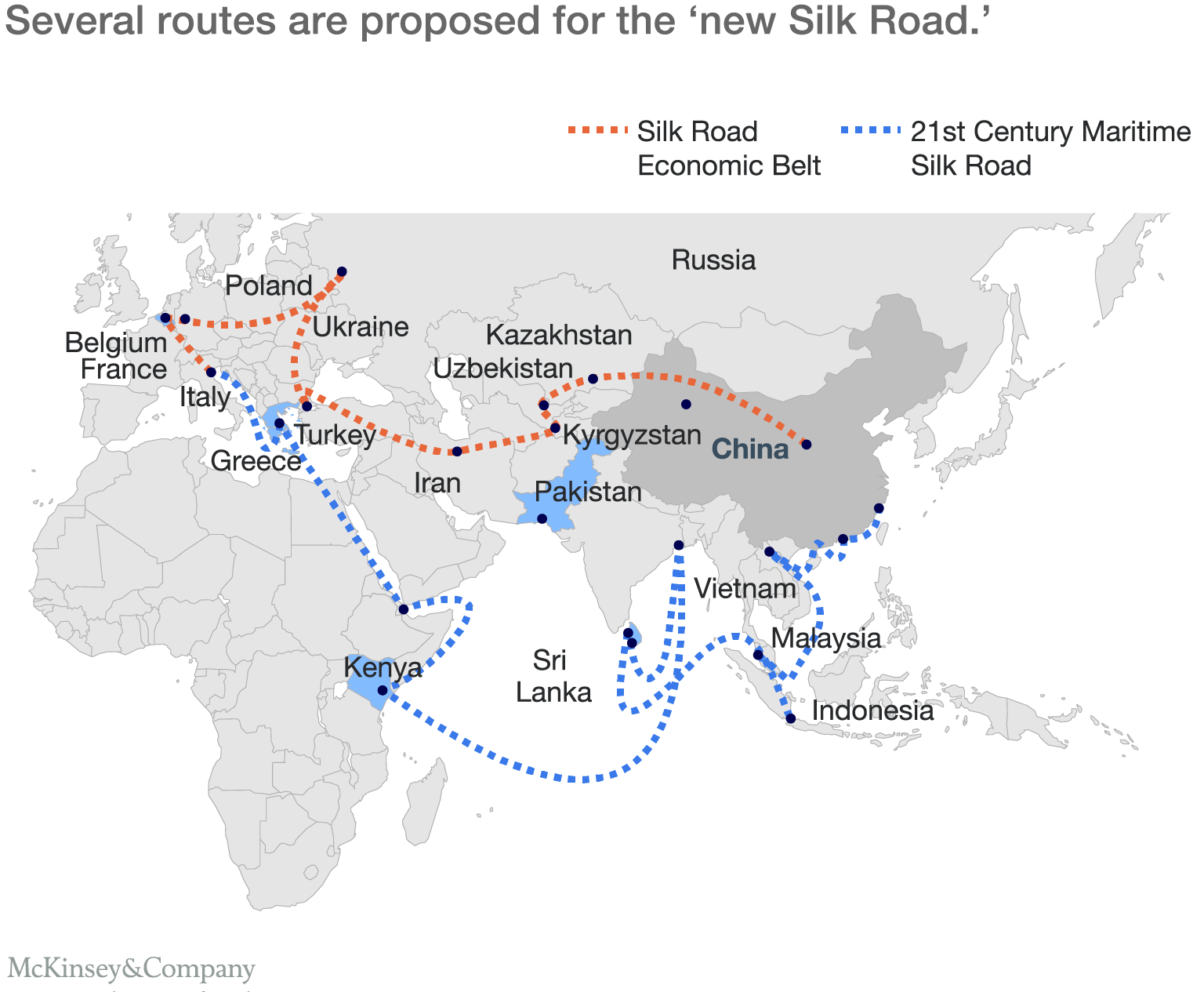

Among various China’s interests’ penetration in global affairs (political, economic and military), there are some China’s specific national priorities affecting global economy and policy’s issues. For example, a multi-faceted “silk road” project has already impacted economies in numerous countries around the world (see the map below).

Conclusion

The first article depicts changes in both the national development paradigm and global governance structures reflecting modern socio-economic and political challenges. On a national level, main attention is given to new paradigm of political economy reflecting modern “transitions”, such as digital, climate change, sustainability, etc.

On modern global transformations, main attention is devoted to the new patterns in geo-economics and geo-politics. Most states and global regions are inspired to translate their existing resources (natural, scientific, human, etc.) into actual power and influence in the world.

The transitions in geo-politics are, generally, reflected in the “blocking” structure of political governance: i.e. besides the process of “uniting” states on various occasions, there are some “regional blocks” that are gaining importance, e.g. G-7 and/or G-20 groups, the EU-27 and others in Asia, Pacific region and Far East.

Besides, although complicated, some inherent connections between geo-politics and economics suggest a cardinal transformation in the mindset of governing institutions on national and international fora. It is becoming an apparent trend that the states are inclined to go into by-lateral cooperation rather than indulging into more complicated international ones; they are willing to “reset” these relations in line with the growing nationalism.

Modern triple transition in national political economy (i.e. climate change actions, digital economy and sustainability) has forced governance structures at all levels to adapt to modern global challenges.